Is There a Back to the Wardrobe?

The movie Shadowlands is a fictionalized story of the relationship between C.S. Lewis and Joy Gresham. Joy was an American writer who had started exchanging letters with Lewis. She later came to Britain on holiday and met with him before returning again to escape her abusive and unfaithful husband. They married so that she could legally stay in the country. Shortly after being married Joy was diagnosed with cancer. Through this experience Lewis discovered that Joy was not just a pleasant intellectual companion but that he truly loved her. Joy briefly went into remission in which they were able to enjoy this love before dying.

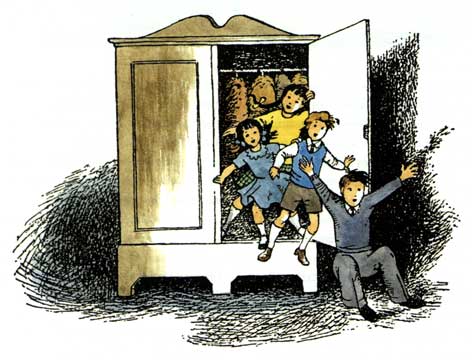

One of the most potent symbols in the movie is the wardrobe in the Lewis’ attic. It is possible that even the writers of the movie did not realize its full impact. When the Greshams visit the Lewis house for the first time Douglas, Joy Gresham’s son and a reader of the Narnia series, discovers the wardrobe. His first glimpse of it is filled with boyish wonder.

Later they return to the Lewis’ for Christmas. Returning to the wardrobe Douglas finds that someone has left it unlocked and slightly ajar. At that moment I felt as curious as Douglas. Like him, I wanted to see what was inside the wardrobe. Did it lead into another world?

And yet, I knew that this was not a fantasy movie. They wouldn’t, they couldn’t have the wardrobe be a doorway to Narnia. It would have been too expensive, too distracting from the plot. So no, he mustn’t open the door, because the chances of this being anything other than an ordinary wardrobe were a million to one. As long as the wardrobe were left unopened, Douglas and I would still have that one chance out of million that the wardrobe wouldn’t have a back to it.

Douglas pulls back the doors to reveal thick winter coats. Thank goodness it wasn’t full of dust and open air. Still he and I must know if it has a back. Douglas pushes through the coats with his hands. There are no fir trees, only the firm wooden back. If he opened the wardrobe a hundred times and felt through the coats the result would be the same.

After Joy dies the movie finds Douglas sitting alone in the attic. He sits in the dark while the wardrobe is illuminated. Lewis joins him and they both start sobbing (which, if you have read Douglas Gresham’s introduction to A Grief Observed then you know this is pure invention). There is no need to look in the wardrobe now; they both know it has no back. Any illusions of goodness, beauty, and wonder in the world are just that, illusions.

Lewis mentions his struggles with God after Joy’s death in A Grief Observed. Some of what he wrote can readily be described using the language of the wardrobe. What Lewis feared most in his grief was not that he would come to doubt God’s existence, but that he could turn God into something he was not. Was God an impotent fool, unable to prevent evil and suffering in the world he created? Are stories about God working great miracles in tragedy and magical wardrobes bright placebos to help us cope with suffering? Or what if, wondered Lewis, God is the great cosmic sadist, the vivisectionist who enjoys dissecting live animals. He promises us beauty and goodness, only to laugh when we find the wardrobe empty.

It may seem like the question of whether the wardrobe has a back or not is unimportant. However, in good art, imagination mirrors reality. For someone who so often grasps truth imaginatively, the question is potent. Understanding truth imaginatively has the power of bringing it from savoir to connaître, knowledge of the facts to a living familiarity.